Polyglot

Have you ever met anyone who’d unlearned how to swim, how to ride a bike, how to dance, how to kiss? (Leaving aside diseases or serious accidents, of course.)

I wish languages belonged to this type of skills that you learn once and forever. But, alas, they do not.

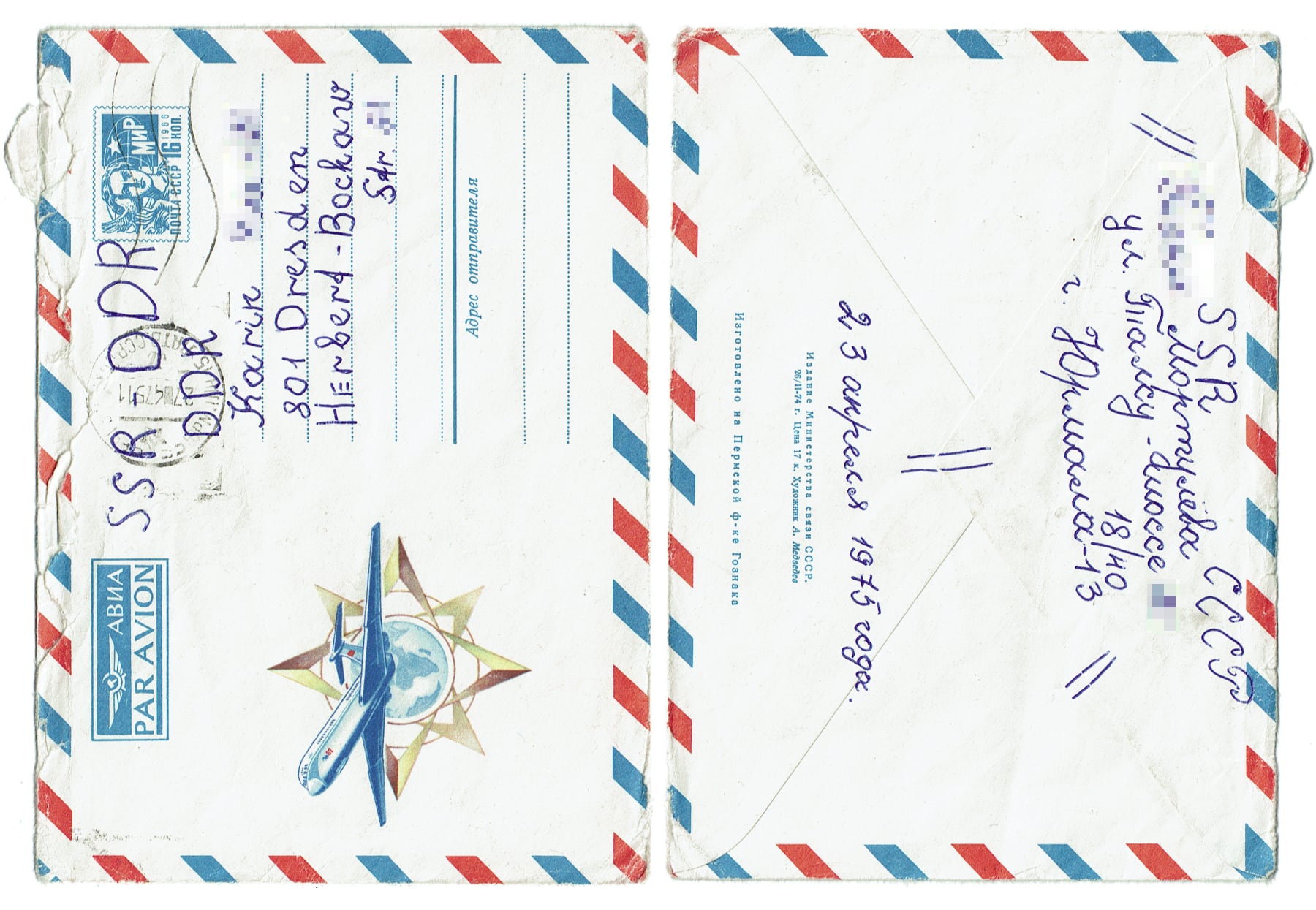

During my school career, I had the opportunity to acquire four foreign languages: English, Latin, French, and Russian. And I was good at languages. But what’s left today? I flatter myself to read and write English quite decently and to speak it not too badly. But French – well, I can follow texts (with very frequent recourse to the Dictionnaire) but would struggle hard to keep up some small talk. It’s like I’d never had all those French lessons at school. And Latin? I can discern the roots of some fancy specialist terms, I remember the logic (and beauty) of ablativus absolutus but I could not even dream of reading Cicero again or writing some prose myself. Russian? I can still decypher Cyrillic letters. But there’s not anything left from almost three years of learning but some single words.

I always found it vexing to think of having had command of a language and then having lost it. So vexing was the thought that I was taken by a rather whimsical idea: must not all those vocables and grammar rules once acquired still reside somewhere in my brain? Crammed into some corner among cobwebs and the binomial theorem? And must it not be possible to recover them rather effortlessly by reading a book? Say, I buy a Russian textbook, skim it casually and – bang! – with one stroke all my long-lost Russian vocabulary is back! Doesn’t this sound intriguing? To me, it did; and it sounded plausible too (you only need to really want something to sound plausible, you know …).

Very surprisingly, it did not work.

No, there’s no way around it: languages is something you must use – passively and actively, and regularly. This does, by the way, apply to your own native language, too (as many sad publications, from tweets to newspaper articles to heavy tomes on sophisticated subjects prove – which, however, is quite another topic …). But isn’t the effort you must invest to gain a language part of the joy? (And note: this remark comes from quite a sluggard.)

Just recently, my Italian friend Gianluca and I – excited by how excellent automatic translators (like Deepl) have become – quipped about why to learn a foreign language at all. We were just joking, of course. Translation software and apps are one of the very valuable gifts of Information Technology to us ordinary people, no doubt. But those apps cannot be a replacement for the real thing – not as long as we are human beings with a heart and a soul.

Apart from the subtle details, the nuances, puns, and overall richness of the language (or even the sense of a phrase) that still get lost: the joy of extending your vocabulary, the euphoria when using the acquired language in real life for the first time, when overhearing a chat of foreigners on the train and really understanding something of it, or when reading your first novel in that language – you cannot have it by skipping the process of learning.

And you can never get as close to people by using an app as by really speaking their mother tongue, however imperfectly. It’s the type of difference like between smiling at a person and sending them an emoji.

I envy friends who have command of more than one foreign language. And who, maybe, speak a dialect of their mother tongue, too. But it’s never too late to learn. Top on my list is Spanish. And refreshing my French, of course. And I would like to acquire a glimpse of the Polish language, too, and maybe Korean, and Hebrew, and … Well, you see what my problem (besides idleness) is.