Inventory

When you see our media abuzz with all sorts of reflections on East Germans and West Germans and their respective peculiarities and flaws and merits, about what went wrong between them and when and why, and about if we weren’t better off had the Berlin Wall never been touched – when you see all this there can be no doubt: it’s the 3rd of October again, German Unity Day, and you’re witnessing our very German way of commemorating that event.

And since I’m not only a German but as a Saxo-Westphalian East-West hybrid combine the quirks of both parties, I feel entitled to add my share to the spectacle, too.

Don’t get uneasy, though: I’m not going to bother you with more kitchen sink psychology or a repetition of the long list of woes and problems, real and imagined. Everything has been said about what has made reuniting the two Germanies after four decades so complicated and protracted a process, right?

But while it’s a good thing to know the problems you’re facing it’s another question why sometimes we simply go and try to solve them (or come to terms with them if it’s the kind of issue you cannot do anything about) and at other times we sit down and confine ourselves to ranting and wailing.

In the case of the German reunification, the root of today’s widespread despondency and downright clinical obsession with things awry might be that, at the time, both East Germans and West Germans thought they were doing one thing while they actually did another. What both sides missed was that reunification didn’t only mean the end of the GDR but also that of the Bonn Republic. (I’ve noted this as an aside already when commenting on the book »Die geglückte Demokratie« in my literary review of 2020.)

East Germans were at least conscious of leaving their old world behind and entering into something different. However, they failed to realise that different in this case meant new. East Germans assumed that they were going to join the Bonn Republic. And this was what West Germans tought, too. Thus, West Germans didn’t expect any changes at all concerning themselves. The whole thing would cost some money, sure (though, back then, only few people seem to have had a realistic idea of the numbers), but all in all the world would roll on exactly like before.

The reunited Germany, as a consequence, was a new entity that was taken for something that it had actually replaced. A country whose inhabitants thought they were living somewhere else: in a country of the past.

This might sound like splitting hairs, especially as the reunited Germany had a lot in common with the Bonn Republic. But this self-delusion did not only carry in it the seed for disappointment and regret that would sprout in the sobering moment of realisation. It also prevented the building of a strong base for the new country by consciously answering questions like »Who are we?«, »What’s different from before?«, »What do those changes mean for us?« – The self-delusion deprived the new country, to put it with some pathos, of a founding myth.

Part of such a myth could have been the revolution in the GDR (epitomised by the word Nikolaikirche). But, alas, those thrilling, magic, history-making events were perceived as something Ostdeutsch, as something rather exotic, pertaining to East Germany only. (Just like, to widen the view, the revolutions in Eastern Europe and the fall of the Iron Curtain were seen as something Osteuropäisch and never really became part of the self-conception of the European Union.)

A solid common base, a founding myth could have been a source of optimism, of energy, of patience. Without it, differences seem more pronounced, problems look graver, costs feel more burdensome, and conflicts turn acrimonious quickly.

The English and the Scots faced similar problems after the merger of the two kingdoms in 1707. Don’t get me wrong here – I don’t want to add to the towering pile of untenable historical comparisons and interpretations (see my article Roaring Again?). For starters, the Scots and the English had had the bad habit of knocking in one another’s heads time and again – which does not apply to East and West Germans (who, instead, jointly turned against other people and knocked their heads in, which is why there was two Germanies in the end …).

In 1707, anyhow, an impoverished, sparsely populated Scotland merged with a rich, powerful and populous England (and Wales, for that matter) into something that was neither Scotland nor England but the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was neither a love match nor an untroubled wedlock afterwards. In his book »The Isles«, Norman Davies writes:

Yet the Anglo-Sottish partnership in union and empire had been achieved through political necessity. It was not underpinned by history, by culture, or by popular enthusiasm. An imperial British state had been brought into being. The more formidable challenge was to forge a community of people inspired by a strong sense of common identity and purpose – in other words, to create not just a British state, but a British Nation.

Considering, though, that even today the relations between English and Scots are still not entirely cordial and every now and again Scottish independence looms on the horizon, this analogy might be unfortunate not only for its historical inaccuracy. And as for the German reunification and the chance to forge, as Davies puts it, a common identity and purpose, it’s no use anyway shutting the stable door when the horse has already bolted …

The united Germans did without a clean relaunch and have to cope with the resulting difficulties, some of which are real and tricky while others rather belong to the category »Get a life!«

And if you ask me what I’d have done had I been in charge back then in 1990 – well, I’d have called the Filmindianer of the East, Gojko Mitić, and the Filmindianer of the West, Pierre Brice, and ordered them to make one movie together, both starring in the leading roles: a pair of twins from a Plains tribe – Siksika, say – who get separated as childs and, after many adventures and dangers, meet again without knowing … – well, you get the gist. The one great, soul-stirring, inspiring, ultimate Indianerfilm for kids on both sides of the Elbe. That’s what I’d have done.

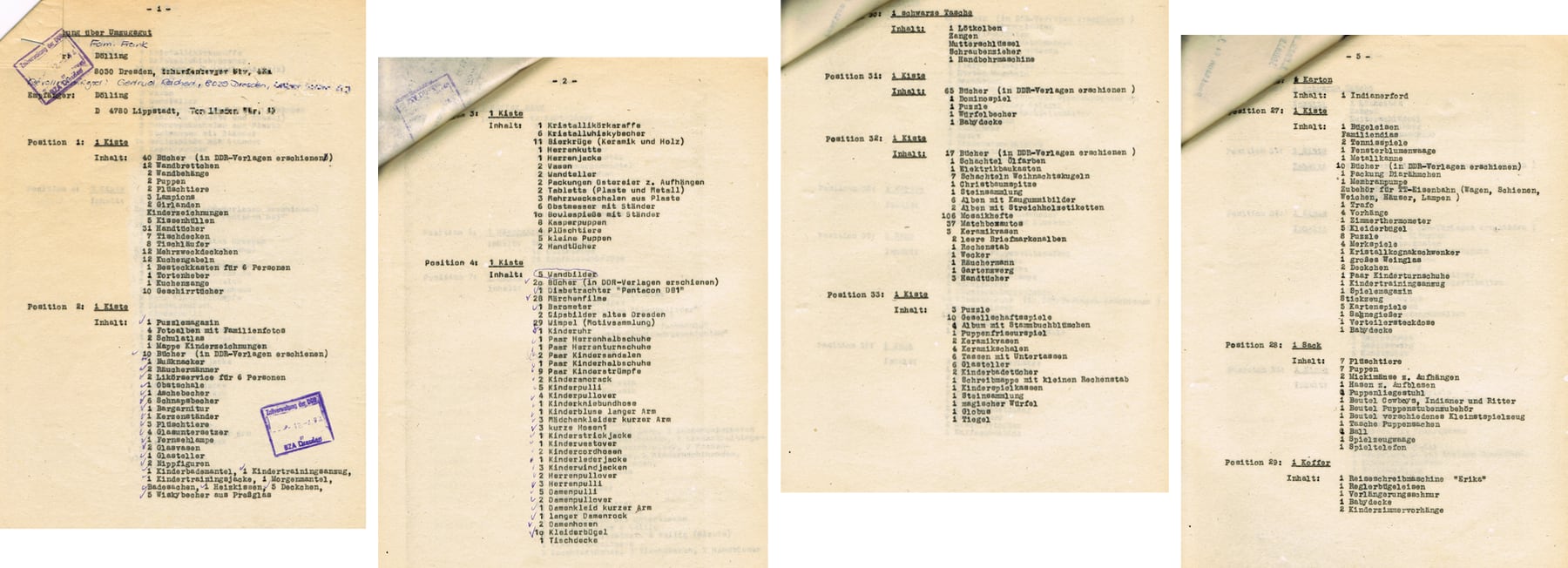

About the photo above: One possibility to leave the GDR was to file an Ausreiseantrag, that is to apply for an exit or emigration permit. You needed a reason (relatives in West Germany was the one most commonly given), a lot of patience and guts. Then, after a totally arbitrary waiting time and some more or less severe harassment by the authorities, the day came when your exit permit was granted. It came along with the withdrawal of your citizenship and the order to leave the territory of the GDR within 24 hours (failing which you’d face arrest as a stateless person). – My parents applied for the emigration permit in 1982. The day when the police came to tell my parents to leave was in March 1984. Twenty-four hours for a couple with two kids to handle all necessary formalities; to say farewell to dear people (which back then meant a farewell for an indefinite period of time or even forever); to organise the trip (via a ramshackle railway system with uncooperative personnel); to pack the things to take along on the journey; and to stow into crates and boxes everything that they were allowed to send after them to their destination in the West by a Western haulage company. (The company, by the way, took only Deutschmark, thus forcing my parents to incur their first – and considerable – debts; and it was, as it turned out later, run by the GDR authorities). And as if this was not enough, my parents had to make a detailed inventory of everything those crates contained. Just imagine: under immense pressure of time, anxiety and the pain of parting, they played some kind of Tetris trying to optimally pack as many things as possible into the available boxes while adding every tiny piece to the list with an old mechanical typewriter (without undo functionality, to be sure …). – My parents still have all the documents from that time, including said inventory listings. You can see some of them on the photo above.