Things Tangible

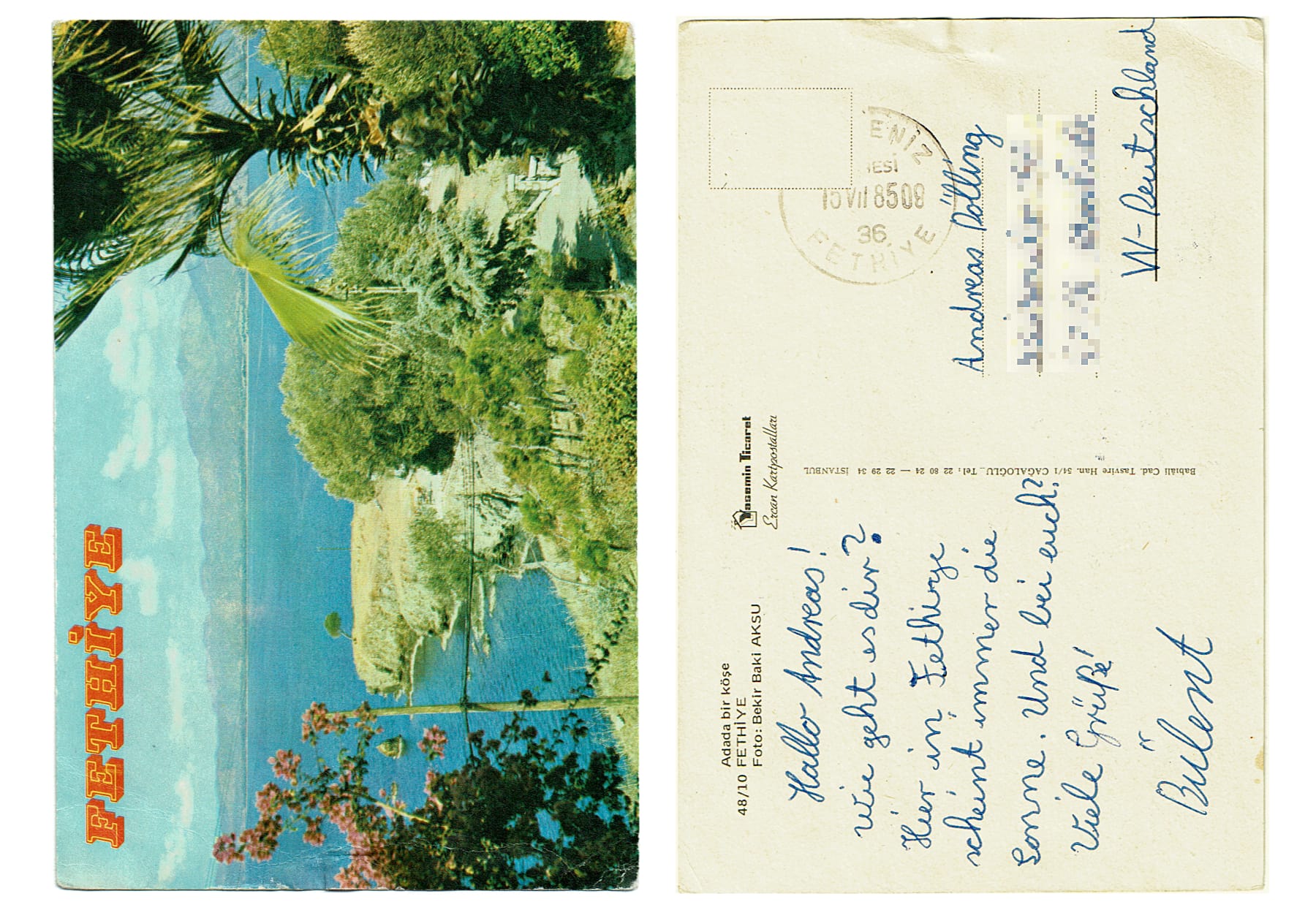

Bülent was my first friend in the new home town after my parents, my sister and I had moved to a new country leaving me with exactly zero friends quite suddenly. And he was the first boy with such a strange name and with such an exotic background I had ever met until then. (Probably he found my background just as exotic …)

For some years, say between age 12 and 16, we were best friends. Then, by and by, our connection loosened again until our ways parted.

What was it that made us friends? Intercultural interest? A conspiciously cosmopolitan mindset? Some other lofty idea driving us? – Nope. It was much plainer. It was what we had in common: we lived in the same tenement block, our families had a similar economic background, we shared the same language and some basic notions of what was good and what was not. And we were enthusiastic about »The Alan Parsons Project«, C64, and role play games. (Counterintuitive trivia: we were both bloody good at sports nonetheless!)

That’s about it. Plain and simple: a common basis and just enough congeniality – and no nationalist or religionist chauvinism nor bullshit blather from the better quarters or the ivory tower.

What many do not get their heads around is that – despite all our (assumed) intellect and evolutionary refinement – as social animals we thrive in local contexts and are more comfortable with the tangible and familiar than with the abstract and global.

This does not prevent us from making friends with people from the other end of the world or from very different cultures. Not at all. But we do need some links, something reciprocally connecting. Without, there cannot be friendship.

So, naturally, you cannot love everyone nor even be friends with everyone. (Not even Jesus could.) There will always be those you feel connected to – and the others. This does not have to be a problem though. We need not and we should not try to transcend our local sociotopes into some abstract world culture and community. No.

We just have to make sure that we all get along with each other. And this can only be achieved by a common ruleset, by clearly defining what is private and what is of public interest and by a readiness to compromise combined with a decent dose of good old self-discipline. Clearly, such a ruleset should comprise only a small number of very basic and very concise items, leaving no room for interpretation and exegetical hairsplitting. The most important item should be the Silver Rule: »Do not to others what you don’t want them to do to you«.

This is what, in my opinion, we can and should attain.

Again: it’s okay not to like everyone, it’s even okay to dislike other people or to be prejudiced (we all are, even the wiseacres from the ivory tower). The crucial point is that we all stick with the rules and get along – if only with »stiff upper lip« now and then. This is not such a brilliant ideal as striving for a society where everyone is deeply interested in and filled by genuine sympathy for the habits and culture and views and cuisine and whatnot of everyone else.

But it works. And it lets us tell more easily who is bad.

Friendship cannot be decreed. As said above, it takes a common base, some congeniality and absence of nationalist or religionist chauvinism. (What it does not need: bullshit blather from the wiseacres and zealots.)

Reads: For more – many more and much deeper – reflections on the Silver Rule and reciprocity versus asymmetry in all spheres of human life, I strongly recommend Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s books, especially »Skin in the Game«. And as for the inner workings of human beings as social animals you should – as a lay reader – find nothing better than Robert Sapolsky’s »Behave«.