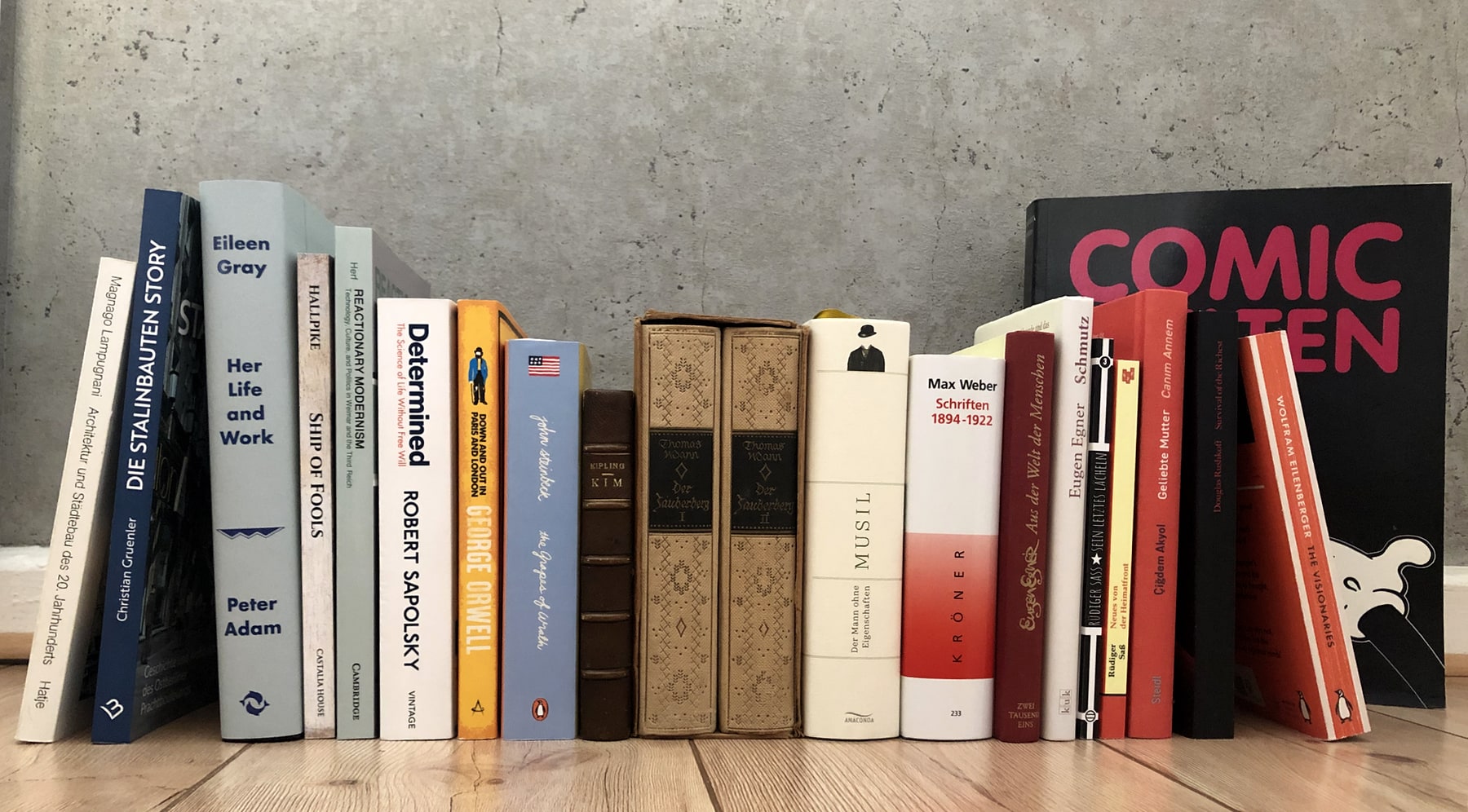

My 2025 Reads

A Eulogy Continued

After what I wrote in August last year, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that as my best non-fiction read of 2025, I name Robert Sapolsky’s »Determined«. Four hundred pages brimming with scientific detail and permeated by the enthusiasm with which Sapolsky puts forward his conclusions – conclusions, fascinating, comforting and unsettling at the same time.

As some evolutionary biologists have pointed out, the only way humans have survived amid being able to understand truths about life is by having evolved a robust capacity for self-deception. And this certainly includes a belief in free will.

»Determined«, apart from its content, is a fine example of truly humanist science writing in that its author’s clear goal is not to shine but rather to share his knowledge and his ideas and make them accessible for as large an audience as possible. You know those scholarly books that seem to be nothing but a dreary tangle of mile-long sentences, needless jargon and stilted expressions, right? Well, Sapolsky, instead, welcomes his readers with casual narrative, self-irony and warmth (while still conveying the facts).

A Little Excursion and Then Back on Track

My impression, by the way, is that it’s German non-fiction writers who are particularly prone to the more baroque, convoluted style mentioned first. It’s much better today than fifty or a hundred years ago, no doubt, but that strange urge to apply one’s words more on showing off one’s learning and status than on spreading wisdom still seems to be a woefully widespread vice. Is it the fear of losing one’s repute among the academic peers by sharing one’s knowledge with the common rabble? On the other end, there’s an audience who are all too easily tricked and who confuse a barrage of unwieldy sentences (even if incomplete or containing grammatical blunders) and many exotic terms (even if applied in a wrong context) with eloquence and erudition.

I read the works of Max Weber last year – a case in point I should add (though it’s a bit unfair to compare texts from the beginning of the 20th century with current ones). Weber’s style shows the typical symptoms of »academicitis«. But I found the struggling through the many pages was worth it, for Weber touches many interesting subjects, often doing pioneering work, and some of his thoughts are almost uncannily topical. Like what he says about the ecomic ethics of the three monotheist religions or about the professionalisation of politics and its consequences.

Aber es ist ein abgrundtiefer Gegensatz, ob man unter der gesinnungsethischen Maxime handelt – religiös geredet –: »der Christ tut recht und stellt den Erfolg Gott anheim«, oder unter der verantwortungsethischen: daß man für die (voraussehbaren) Folgen seines Handelns aufzukommen hat.

Similarly, Jeffrey Herf’s »Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich« was no walk in the park: as a reader you’ll need some grit but it’s a rewarding effort – a very insightful book.

Just like with Wolfram Eilenberger’s »The Visionaries« (you might remember it from my blog post »Angel of History«). To be more precise: Eilenberger’s account of the lives of the four philosophers Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Ayn Rand and Simone Weil is very readable – it’s just the philosophical details that give me a headache. I’m not made for it (I always admire my friend Ela who can give you lectures about philosophical schools off the cuff). Eilenberger’s approach of letting the four women’s lives pass in parallel before our eyes is an unconventional idea and works very well, not least because it lets become clearer the very different paths they followed philosphically.

Things Edifying

There was more non-fiction but not from the realm of science. Last year – I can’t tell why – my old interest in architecture, design and art revived. It began with re-reading Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani’s classic »Architecture and city planning in the 20th century«, a concise tour de force through roughly a century of European architecture, structural engineering and architectural philosophy.

Then, somehow, I stumbled upon the designer Eileen Gray and bought Peter Adam’s comprehensive biography »Eileen Gray: Her Life and Work« (a beautiful edition by the publishing house Thames & Hudson). Gray was among the avant-garde of the early 20th century, as an artisan and designer first and later as an architect too. She knew Le Corbusier and other biggies of the time (and didn’t particularly like »Corbu«, for understandable reasons). An extraordinary life! (Though one should keep in mind that had she been born into a working-class family instead of into the landed gentry, there probably wouldn’t have been much to write a biography about …). The author, Peter Adam, was one of the very few people close to her. Sometimes his affection as a friend gets the better of his objectivity as a biographer and he can occasionally sound a bit as if Gray had actually invented everything new in design and architecture single-handedly and was consistently ripped off or disregarded by everyone. But who’d judge a true friend for such bias? The book is great!

Eileen had sometimes met Pablo Picasso during his Cubist period, but as usual in her modest and evasive way I could never get her to talk about it, except for one sentence: »Oh yes, he was a funny man.«

Another publication on art that I read, about quite a different sphere, was »Comic Welten« by Harald Havas. It’s a book released as an accompaniment to a 1992 exhibition of the same title in Vienna. »Comic Welten« is much, much more than just an exhibition catalogue – it’s a fully-fledged comprehensive history of comics from 1895 to 1992, covering every thinkable aspect of the 9th Art. I cannot remember when and where I got this book but I’m glad I have it!

Finally, on a visit to Berlin in autumn, the book »Die Stalinbauten Story« by Christian Gruenler caught my attention in a museum shop (it was in the Neue Nationalgalerie). It revolves around a string of tenement buildings (mostly with shops and restaurants on the ground level) that can still be seen in the eastern part of Berlin and that bear witness to a short-lived period in the architecture of the Soviet Bloc: Socialist Classicism – a quite peculiar and somehow intriguing mixture of modernism, classicism and kitsch. When Stalin died, this surprisingly bourgeois »wedding cake style« lost its main patron (it’s also called Stalinist Architecture) and the idea of »workers’ palaces« was abandonded in favour of the much more efficient prefabricated buildings (the famous Plattenbau).

What I find astonishing is how quickly those buildings in Berlin were finished, considering that a lot of hard manual labour was involved. This feat of construction was only possible because many citizens put in thousands of hours of voluntary work – at a time when the normal work day and work week was longer and tougher than today and when shortages of nearly everything were rife. Even in the West, people marvelled at those high-standard buildings popping out of the ground like mushrooms after the rain. Could there be something in Socialism after all…? – But the »workers’ palaces« were much too expensive, even with all the volunteering. And as time went by and the problems accumulated, one could count on the obstinacy and inhumanity of the ruling apparatchiks in the East to by and by quench even the last tiny spark of enthusiasm among the population. The world saw the uprising of 1953 and tanks against unarmed workers. That was Socialism.

Gruenler’s »Die Stalinbauten Story« is a compelling book and richly illustrated at that, with many photos and drawings!

Let’s Talk About Me

My literary 2025 was dominated by non-fiction and here’s even more: two autobiographical books.

»Down and Out in Paris and London« was another accession to my library by George Orwell. He describes the weeks he spent among the poor of Paris in 1929, earning his scarce livelihood as a dishwasher, and his time among tramps and homeless people in London later on. – It’s a book by George Orwell, one need not say more. Read it!

He considered himself in a class above the ordinary run of beggars, who, he said, were an abject lot, without even the decency to be ungrateful.

The other autobiographical publication is »Geliebte Mutter – Canım Annem« (Beloved Mother) by Çiğdem Akyol, not an autobiography proper but a novel in the form of memoirs and presumably inspired by the life of Akyol’s parents and by her own experiences. I was very excited hearing about it, since I very much liked her history of the Turkish Republic, one of my favourites of 2023, but also because I was interested in what Akyol might have to tell about that family with roots in rural Anatolia but also in upper-class Istanbul, about a marriage of two very different persons, about the friction in the family between conservative and progressive tendencies, about emigrating to Germany and trying to settle in in the new home country – well, just everything.

Bülent, one of my best school friends, and Akin, my old friend from university days on, both have a Turkish background. So, yes, I was thrilled and bought Akyol’s book as soon as I knew about it. Reading it, though, was a mixed pleasure. From the stylistic point of view, I’d have preferred a more straightforward narration without time leaps and inner monologues and the like. Such stuff is tricky for an author and can easily spoil a story by overuse, just like too much spice can ruin a dish. Nothing for a debut novel – but that’s just my view.

What I really found disappointing was that Akyol could not or would not do without the old »Us vs Them« and drew a picture in which »the« Germans play the role of the uncultivated and heartless brutes who don’t know how to cook or how to dress, who never smile and who let immigrants do all the hard and dirty work. How would this not annoy me …?

Still, all in all, I don’t regret having bought »Geliebte Mutter«. And I think I’ll come back to it later this year and in a dedicated article elaborate on what I find so disappointing – and why.

Via Grand Trunk Road from Davos to Oklahoma

But hey, wasn’t there any fiction at all last year? You bet there was! Classics galore.

There was Rudyard Kipling’s »Kim« which I really enjoyed – until all that special training and secret service and »Great Game« stuff began. That was when I lost touch with the main character and the story. I remember vividly the deep disappointment when Kim’s mysterious, recurring dream came true – but in an unexpectedly plump way. It was so underwhelming a scene, so banal that I was about throwing the book aside. And that was it. The bottom line? Half classic, half junk. Or to put it another way: I liked the Indian Kim but couldn’t have cared less about the British Kim.

The slackening enthusiasm, however, with which I went through the second half of »Kim« was pure euphoria compared to my prevailing mood while reading »Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften« by Robert Musil. This unwieldy tome is counted among the one or two dozen most important modern classics of German-language literature. The contemporary German philosopher and jack of all trades Richard David Precht, for example, seems to never tire of praising this novel. As far as I am concerned, I wouldn’t even consider »Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften« a novel. It was an utter pain to read – actually, most of the time I wasn’t reading but fighting the book. And believe me, it was only out of sheer spite that I made it to the last of the 1.440 ultra-thin pages! I must repeat my theory that critics commend movies and books of this type simply because they themselves hated them and now try to get some consolation from the thought of all the poor fools they can induce to go through the same ordeal.

It was different with John Steinbeck’s »The Grapes of Wrath«. I rushed through its pages like in a trance. I just couldn’t stop reading and hoping, against all odds, for a good or at least an acceptable outcome for the Joad family. – An American classic, a world classic! And a classic, besides, that touches another topic I’ll probably return to this year: social injustice, and why I think that it isn’t helpful in the least to divide people into ever smaller minorities, to pit them against each other, to try and tweak the common people’s language, to attribute any problem whatsoever to colonialism and racism, and when referring to colonialism, to lump all Europeans together, Brits and Poles, industrial magnates and proletarians.

Casy said gently, »Sure I got sins. Ever’body got sins. A sin is somepin you ain’t sure about. Them people that’s sure about ever’thing an’ ain’t got no sin – well, with that kind a son-of-a-bitch, if I was God I’d kick their ass right outa heaven! I couldn’ stand ’em!«

To complete the quartet of literary classics: I read Thomas Mann’s »The Magic Mountain« for the fourth or fifth time last year. And I didn’t even know that 2025 was the 150th anniversary of Mann’s birthday …

Check, Check, Check

Quite a bunch of books down, huh? And how did all this affect my literary to-do list? It got longer …

On to 2026!