Math and Myth

Our colonial goods store was at risk of running out of coffee – a tremendous threat to the reputation of our small but distinguished house. Up to that point, our family used to import our coffee beans from Nicaragua exclusively, a place famous among connoisseurs for its fine arabica varieties. But at the time my little anecdote is referring to, the said country became embroiled in a bout of turmoil and upheaval. Regrettably, our on-site representative lacked the requisite quick-wittedness and could not make up his mind about which faction to favour in the unfolding conflict. Consequently, our trading post was eyed with distrust by all and sundry and was soon wiped from the map.

I was a young man back then, only a mere twenty years old, but still I was not surprised nor overly shaken by the dire news. Our family of merchants originates from Glasgow and we Scots have never been fortunate with undertakings in Central America …

Be that as it may, my father and my great-uncle – the then heads of the firm – decided that we must act and sent me out to find new sources of supply for our coffee.

I knew that there were coffee-growing regions in South America, in India, and in Indochina. But I resolved on tapping the sources of Africa, not least because the finest sorts, next to those we had obtained from Nicaragua, were cultivated in the countries of East Africa.

So I went on board our ship and sailed without delay. I was in no doubt, of course, about where to turn to unlock the treasure chest of the African lands. Is not the Nile the main artery of the big southern continent and has always been? The Nile! What magic the mere name of that majestic river exudes! Tutankhamun, Moses, Nebuchadnezzar, Cleopatra, the confounded Corsican (who, like always, brought havoc and then ran away), Livingstone, Kitchener (and in his wake young Churchill) – ah! All the mysteries, all the riches of Africa – where else could one find them but at the banks of the Nile?

The attentive reader might, of course, object that I should better have gone to Ethopia or Kenya directly and procured the coffee right where it is harvested. But my reasoning was sound, for our trading house still used (and uses) a sailing vessel for overseas business, a plucky little schooner that was once acquired by my father’s great-great-great-uncle. And as thrift is one of the pillars upon which our family’s modest prosperity rests and as we always proceed by the motto »Don’t buy what you already have«, we stick with our schooner.

With regard to my mission related here, this ruled out a lengthy voyage round the Cape of Good Hope and back. And as for the Suez Canal, the same rule of thrift applied: we would never pay for sailing upon the very waters that are free on either end of said canal. (Besides, it’s a question of honour not to rely on anything a Frenchman has devised.)

Thus Cairo was where I was heading.

I left the ship in Alexandria and went upstream in the boat of a fellah, thrilled by the thought of inhaling the very air that the Pharaohs had once breathed.

Cairo, however, was were the trouble started and everything got out of hand. First of all, the city was not the picturesque ensemble of delicate palaces, venerable merchants’ and artisans’ shops, and cozy bazaars that I had expected but had grown into a bustling hive of virtually blasphemous size and noise and activity. I was utterly numbed and stumbled to and fro without aim and sense.

Those bazaars that I accidentally ran across were but one big disappointment – I could have purchased all sorts of spices, dates, melons, chickens, fish but not a single coffee bean was to be spotted. Never before had I felt so outright helpless and inadequate!

In my dejection, I trudged into a little tavern, sat down in a corner and – instantly smelled that most delightful of all odours: roasted beans, freshly ground and brewed. I looked up, all despondency having fallen from me. »Thank heavens!« I thought by myself. »Praised be this happy coincidence and the good old Scottish blood rolling through my veins; the latter giving me the presence of mind and rationality to take advantage of the former.«

At my polite request, the owner of the tavern appeared at my table. That fellow, such was my reasoning, knew where to get coffee and he would help me to get my share too. Of course, he feigned ignorance claiming not to understand my questions. But I knew my Arab merchant colleagues and their secretive ways and so I insisted. The man prevaricated stubbornly and even proposed I go to a supermarket and buy a packet of coffee or two there. Now, here was a tough adversary – supermarket!

I decided to change my strategy. If he refuses to disclose his sources: why not just obtain the coffee from him? And straightaway my fertile brain came up with just the idea.

»Pray, would you mind playing a game of chess with me?« I asked the man. This puzzled him, but the venerable Arab tradition of hospitality compelled him to oblige.

The reader might wonder what I was up to but may be assured that I was just following the new strategy outlined above and would finally fleece the innkeeper of all the coffee he could possibly scrape together. For I was well read in literary classics and tales and legends from all around the world. Including, of course, the famous anecdote about how the Indian brahmin Sissa, the inventor of the game of kings, duped his monarch and won more wheat (or rice) from him than the whole country could muster.

Soon the two of us sat pondering over a checkered board – though, truth be told, the pondering was on his side mainly while I took advantage of my years at college with several chess matches every week. Thus it hardly needs mentioning that I achieved a swift victory, crushing my opponent’s white force with a mere 187 moves.

He still seemed not to fully grasp what his defeat meant for him, but I knew all the better: following the legendary Indian sample, I had stipulated as my victory prize that he give me one coffee bean for the first square of the chess board, two plus one for the second square, three plus two for the third, four plus three for the fourth and so on for all the sixty-four squares.

The man stared at me with a blank face and got up slowly. It must, by and by, occur to him how dearly that chess game would cost him.

As it turned out, however, the math did not work properly – for the innkeeper came back with just a single little bag containing a meagre two or three pounds of coffee beans, not billions of tons as I’d reckoned and as the legend of Sissa claims.

I had, of course, not taken into account the Oriental proneness to flourish and exaggeration and blindly trusted the numbers specified. Now I was none the wiser and would soon be the laughing stock of the bazaars.

So I fled that place of bitter humiliation, vowed to never set foot on African soil again and reasoned where to turn now. India was ruled out as well because how can a merchant do business with partners who mix up their math with myth and throw fancy figures in your face at will? Brazil had to be where our family would procure our coffee from now on!

Things turned out well in the end. And they are getting even better for our trading house since there are more and more people recently who – as soon as they learn that we convey our coffee and tea and spices by sail and wind – are ready to happily pay the most extravagant prices for our commodities.

Yes, all turned out well. And no one in our family has ever heard a single word about how I once considered myself in possession of many shiploads of coffee in a small tavern in Cairo.

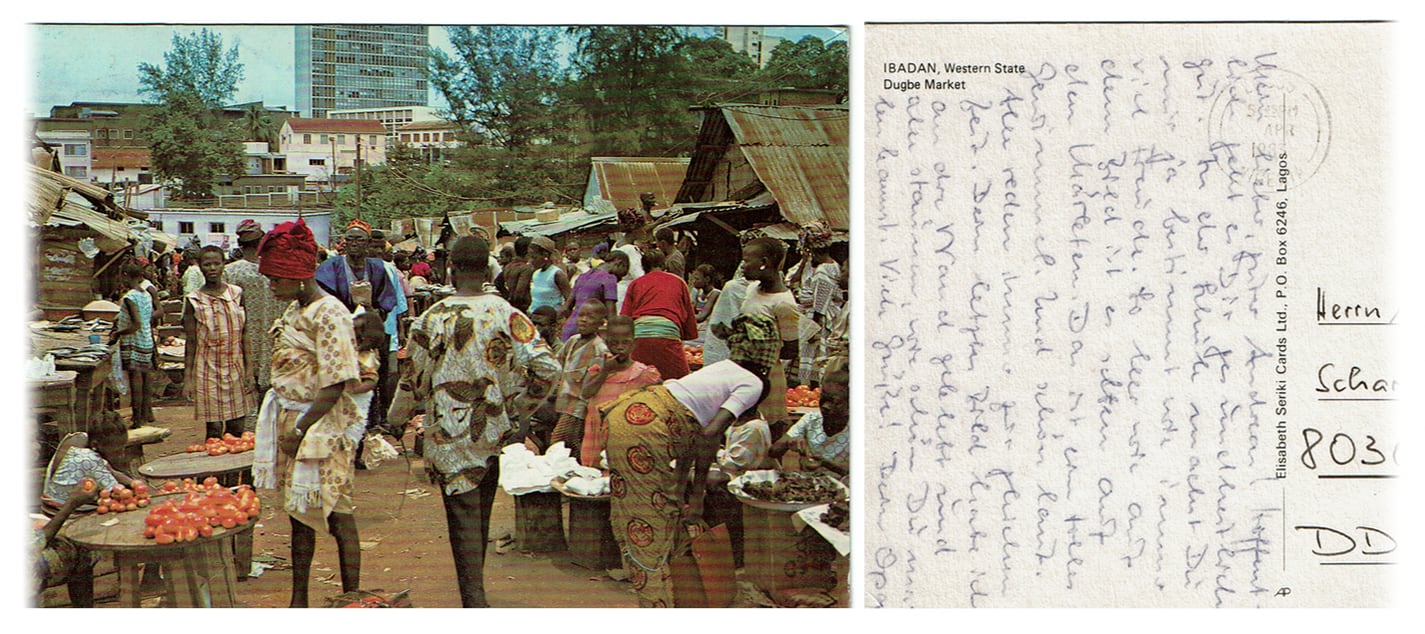

(The postcard above was sent to me by my paternal grandfather. He dispatched it in Nigeria where around 1983 he spent some months doing … – God knows what. He only dropped hints about a splendid business opportunity, something with transportation. During those months it looked like my father and thus our whole family would not just leave East Germany for the Western part but for a destination much, much farther away and much stranger. Thankfully, the projects in Nigeria came to nothing. Else I’d not only have missed my native town and friends and maternal relatives but my native language too – and the beautiful colours of our autumn. We never again heard about any Nigerian projects from my grandfather. Neither of any more projects at all. He was no businessman. I never understood what he was actually – or: who. What drove him? Was his story a sad one or ludicrous? Was he a man chasing after a self-spun fairy tale with himself as the hero? Did he just mess up things and then run away? Was he taken for a ride by someone smarter than himself? Or did midlife crisis make him think that he must perform some heroic feats, preferably in an exotic country? Whatever it was: he might have found his way to Africa, but he never found that into the hearts of people …)